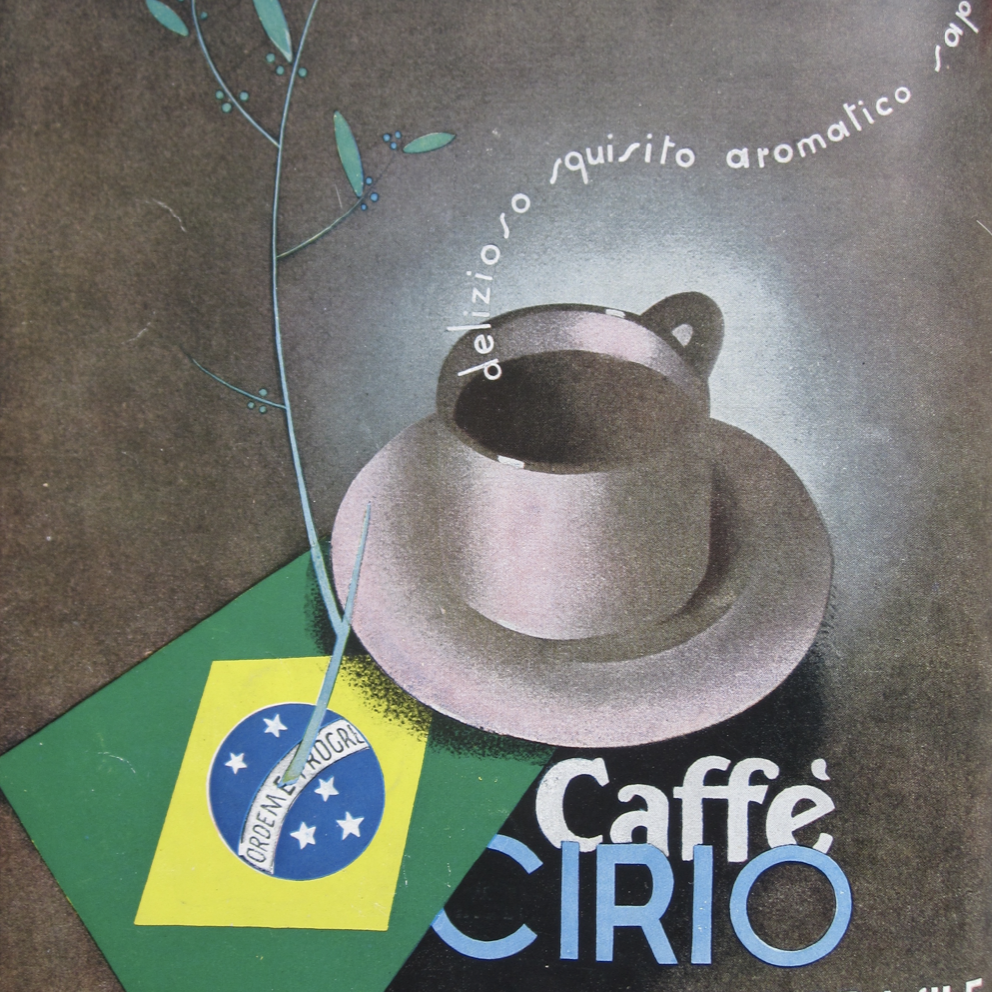

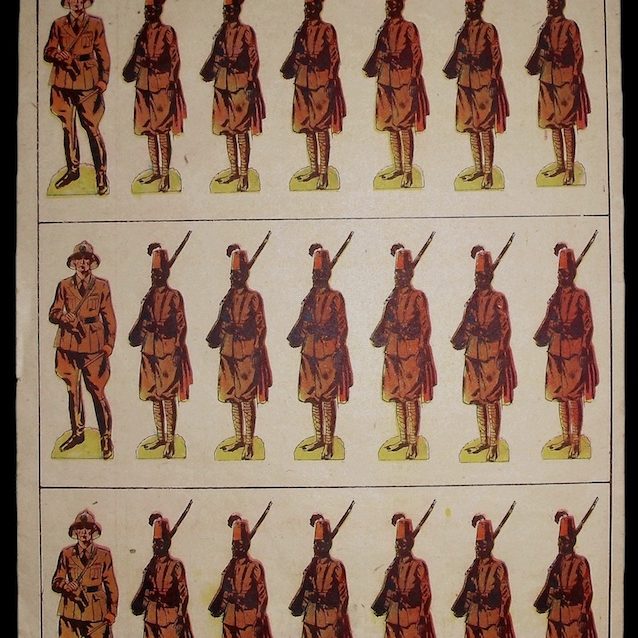

The Italian Coffee Triangle: From Brazilian Colonos to Ethiopian Colonialisti

Commended for the 2022 Sophie Coe Prize, Oxford Cookery Symposium

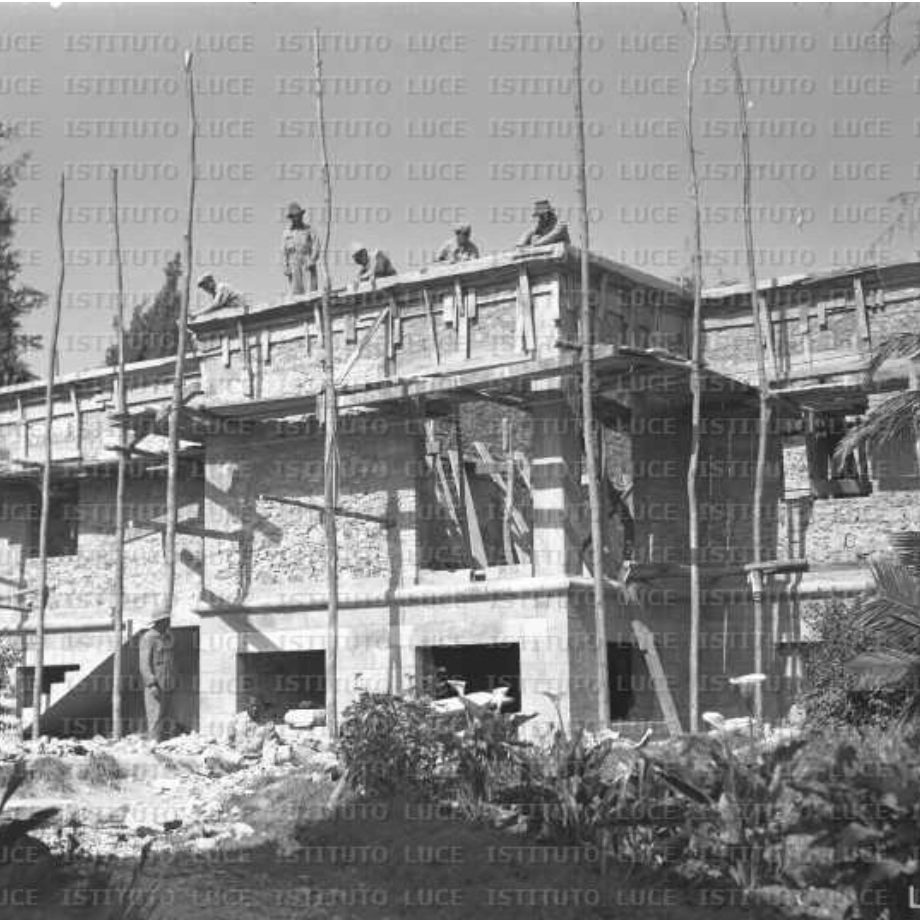

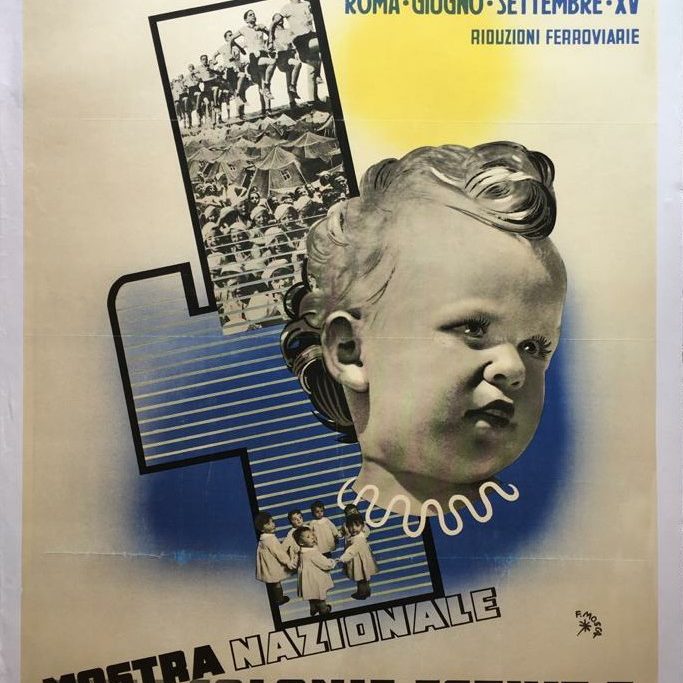

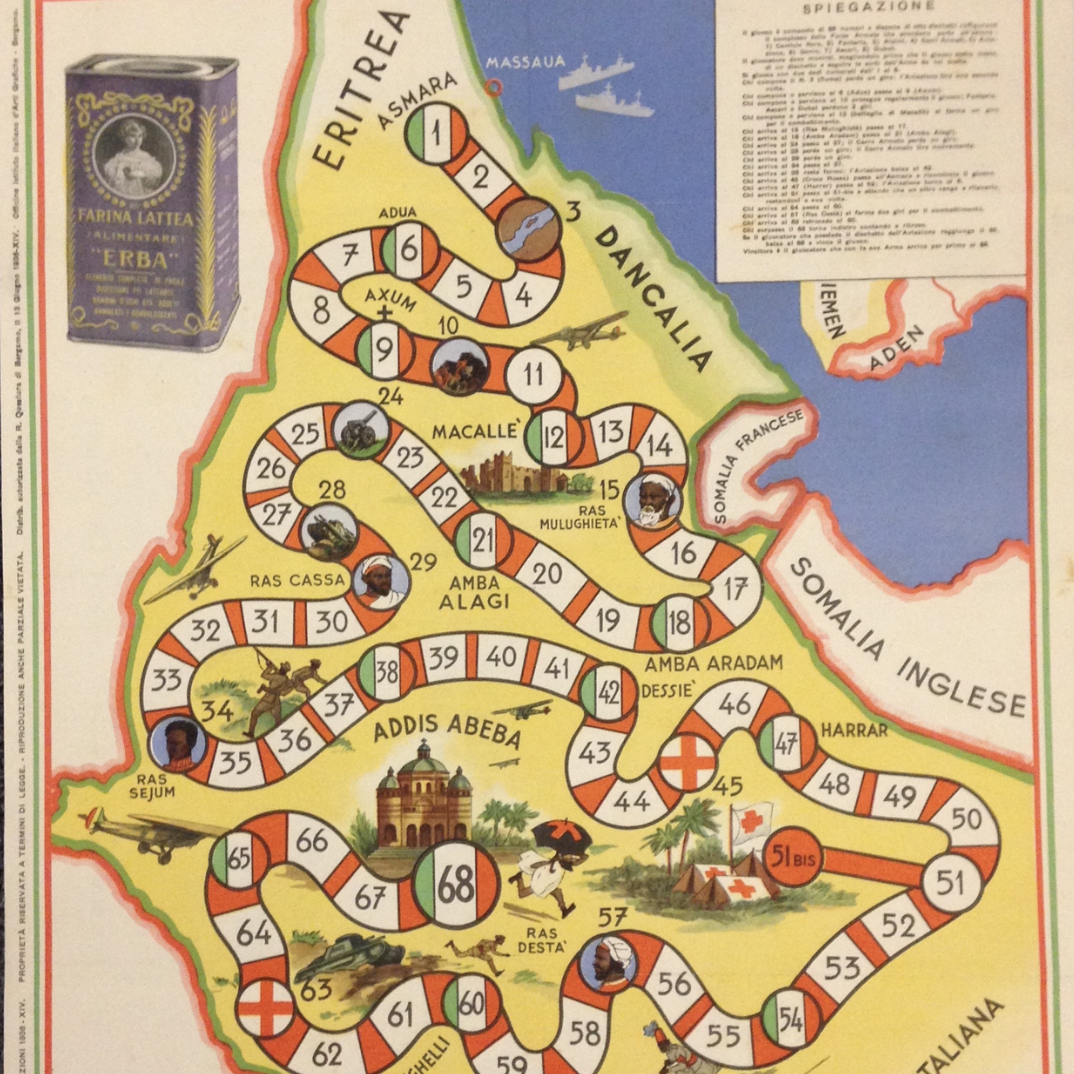

Building Pasta's Empire: Barilla and Italian East Africa

High commendation for the 2023 Sophie Coe Prize, Oxford Cookery Symposium, Honorable Mention for the 2023 Best Article Prize, Society of Italian Historical Studies

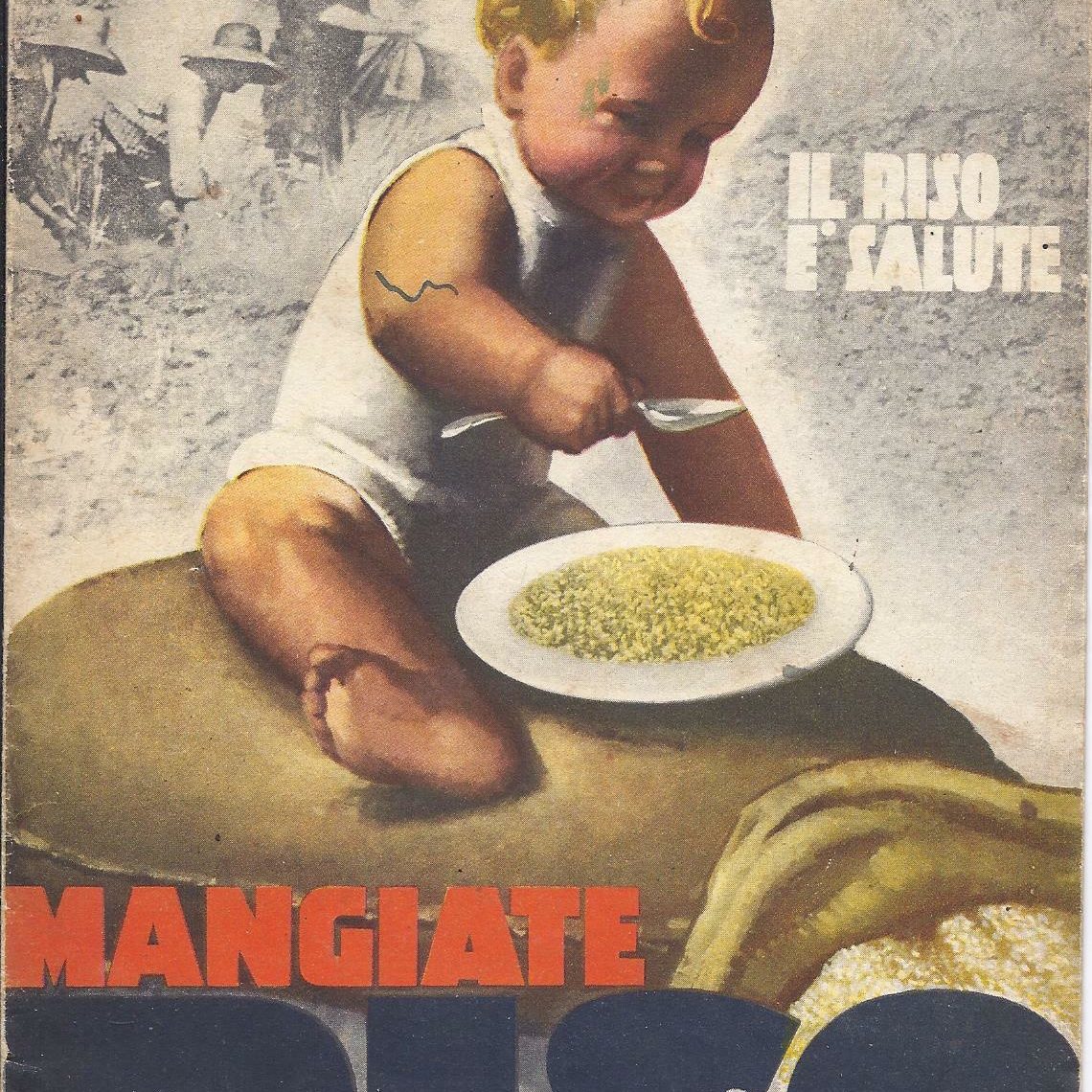

Singing Truth to Power: Melodic Resistance and Bodily Revolt in Italy’s Rice Fields

Winner of the 2017 Russo and Linkon Award, Working-Class Studies Association

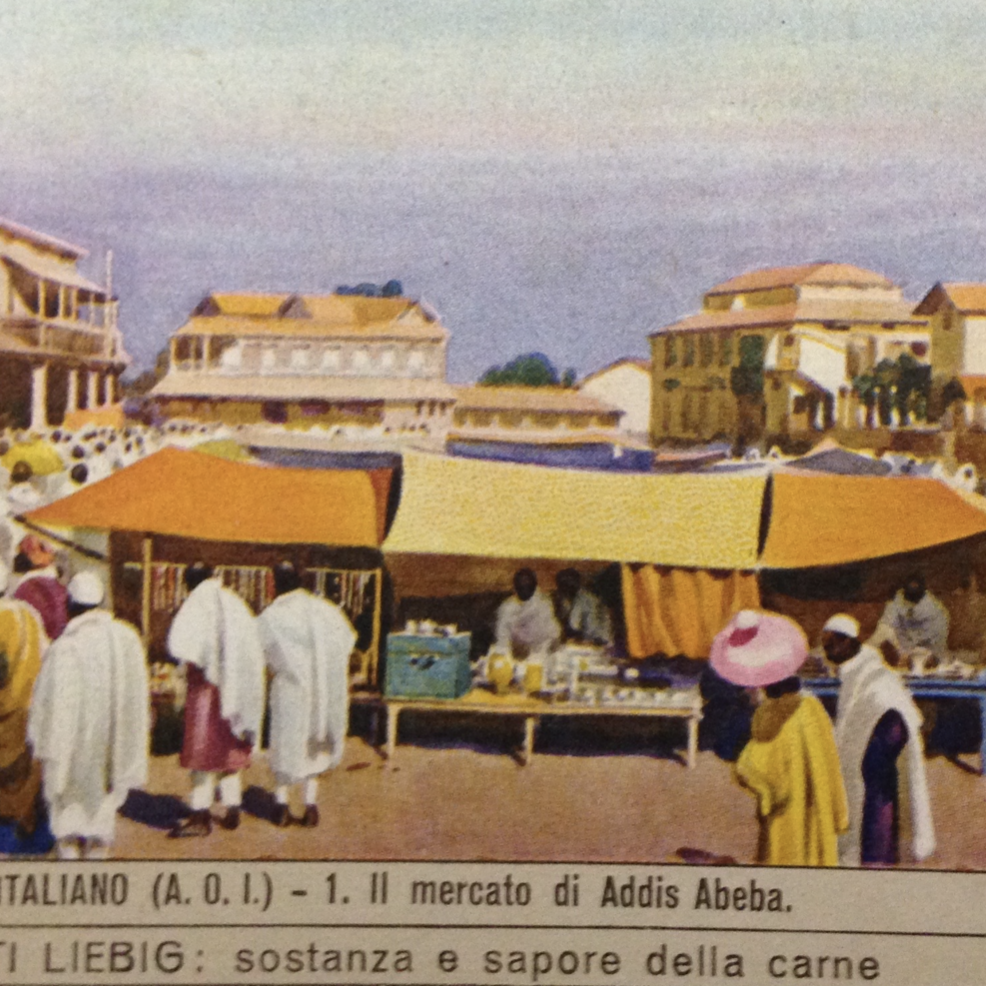

The Pioneer's Feast: Italian Colonial Menus from Eritrea and Ethiopia

Selected for Global Food History journal cover, historical basis for Villa I Tatti banquet

Delightful by Design

Industrial designer Emma Bonazzi designed Perugina chocolate boxes and much more.

Modernity and Postmodernity: Food, Fashion, and Made in Italy

Italian identity just might be the bel paese's most famous export.

Tradwives, Techbros, and the Commodification of the Far-Right

Influencers past and present have used far-right politics to sell their products.

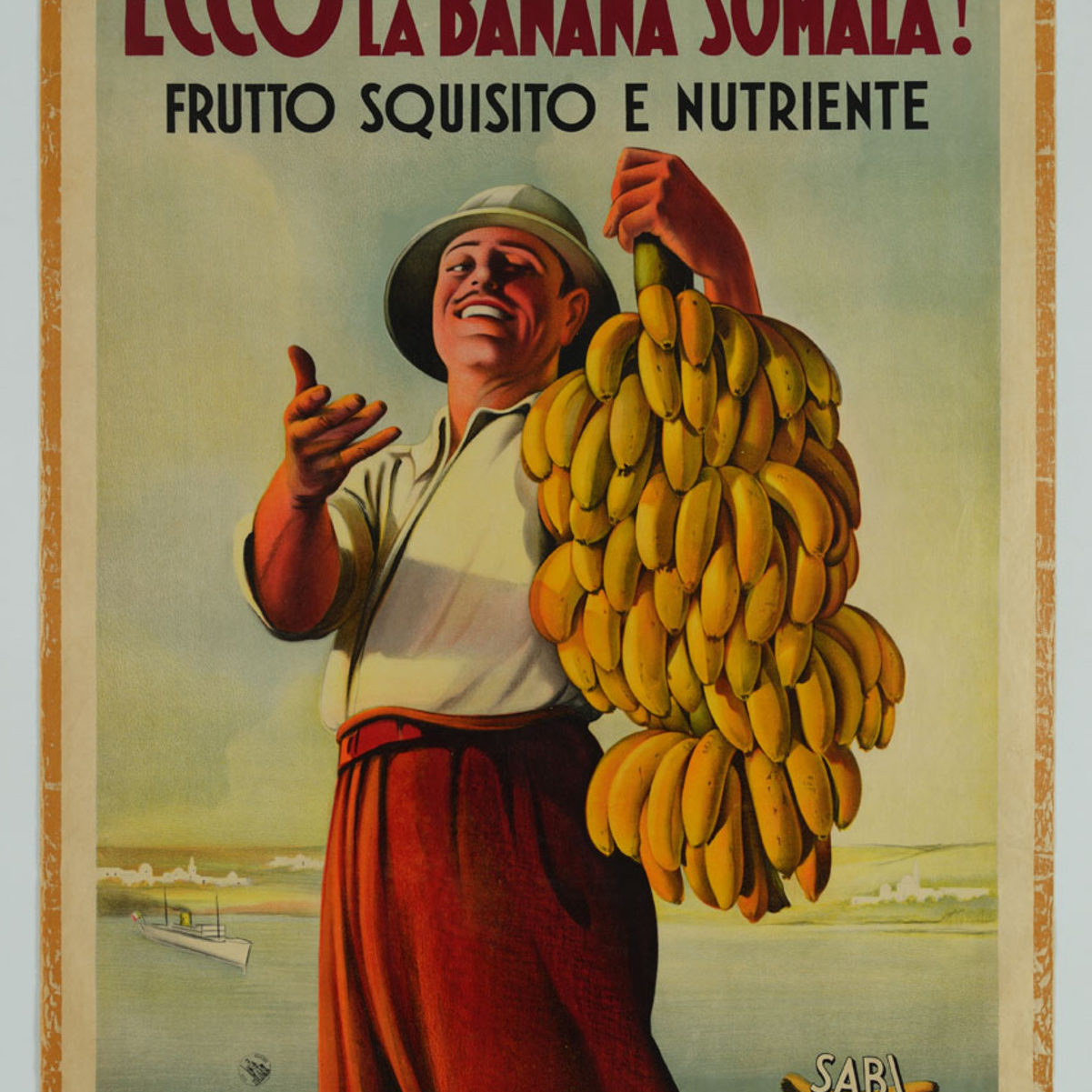

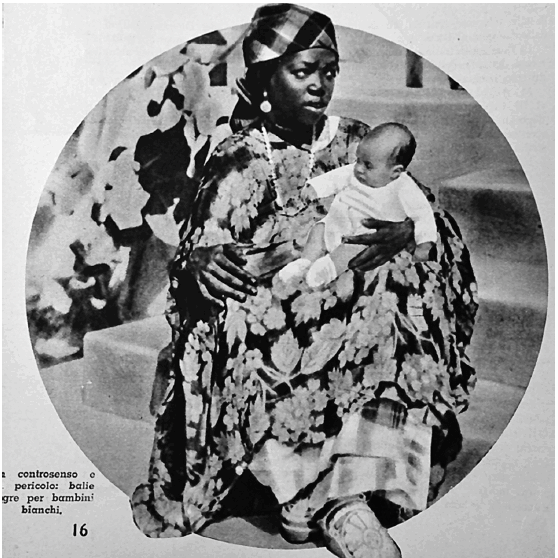

Food and Food Policies under Mussolini

Under Italian fascism, your grocery list was state business.