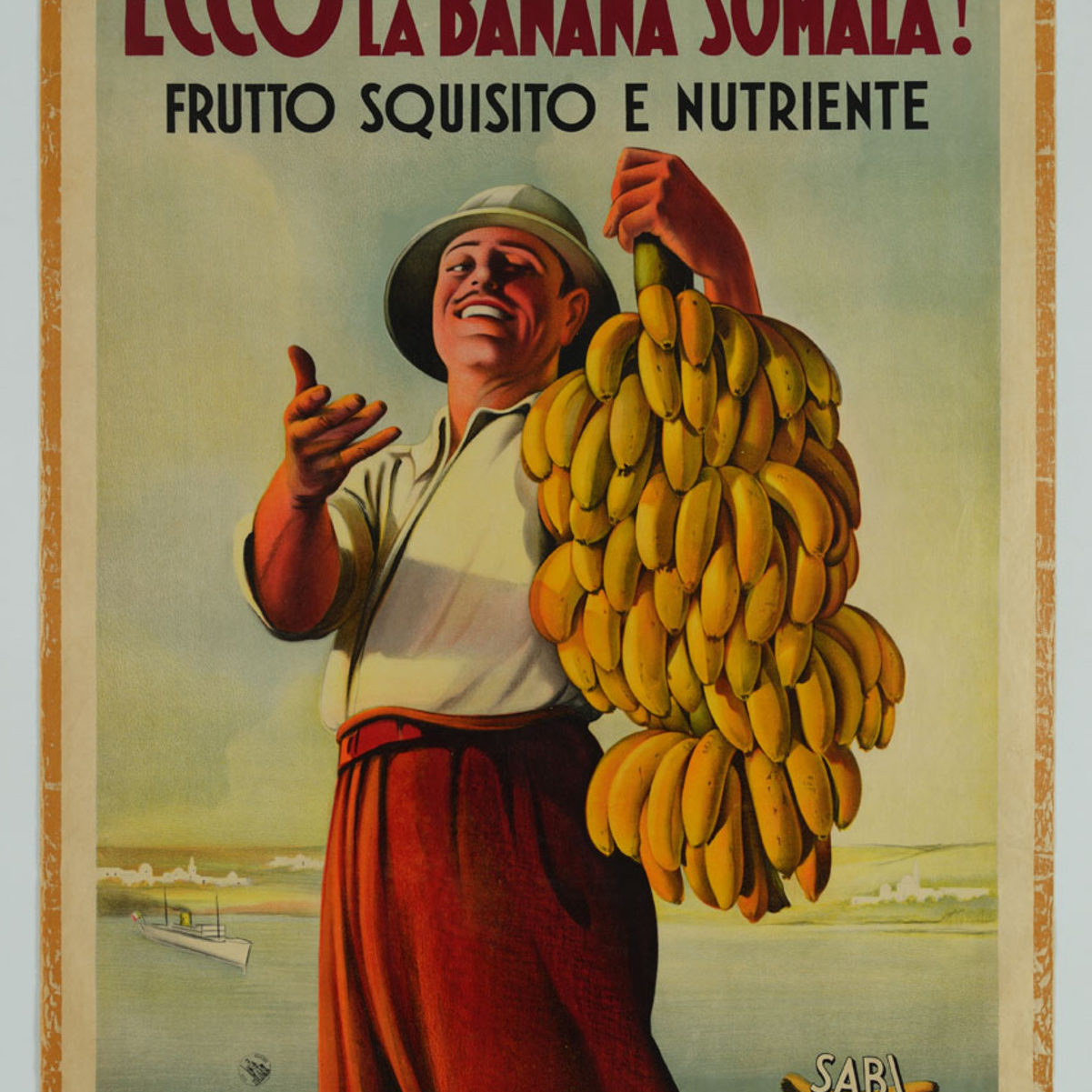

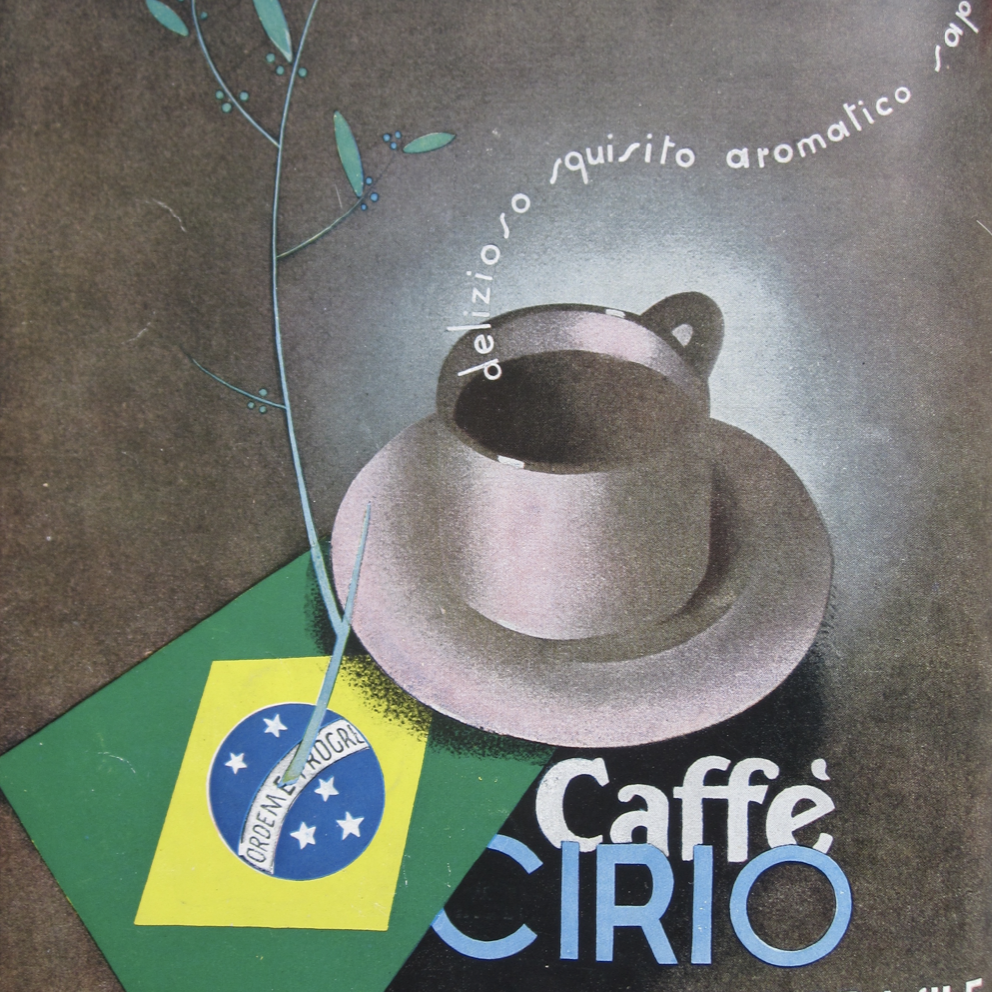

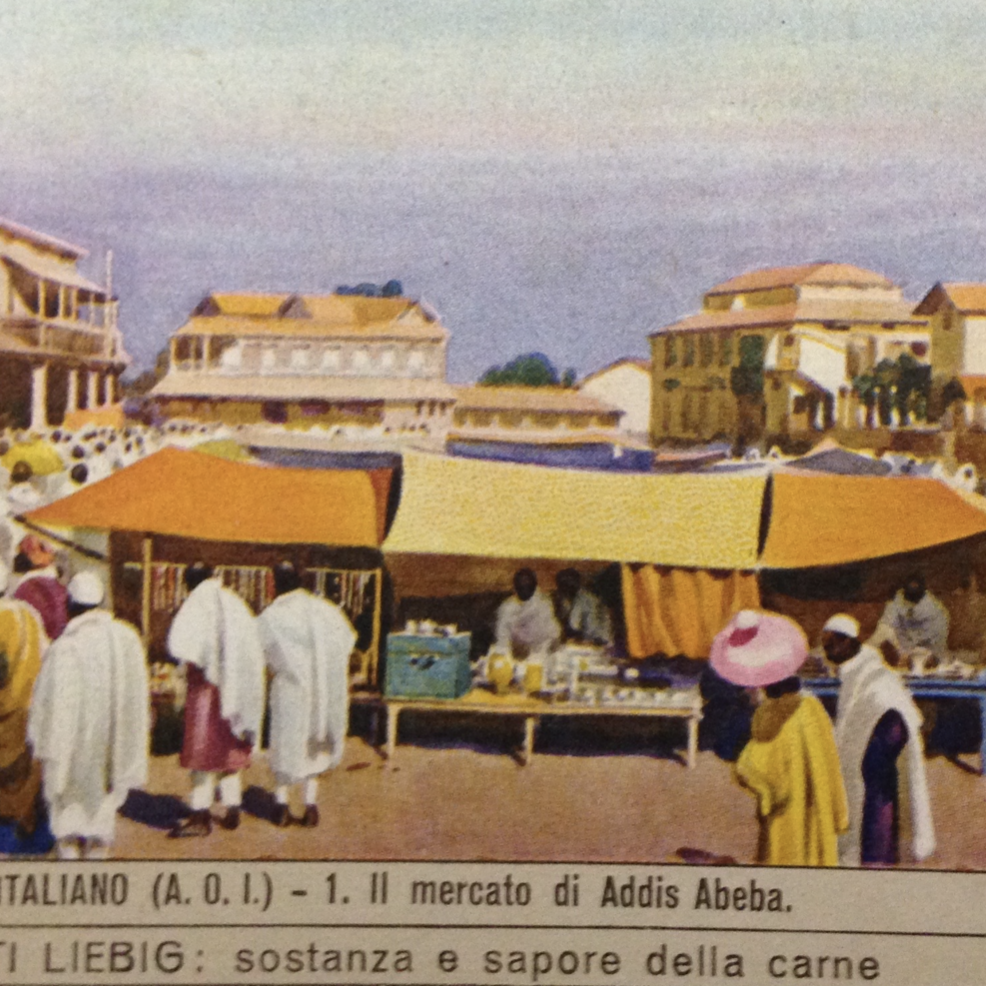

The Italian Coffee Triangle: From Brazilian Colonos to Ethiopian Colonialisti

Commended for the 2022 Sophie Coe Prize, Oxford Cookery Symposium

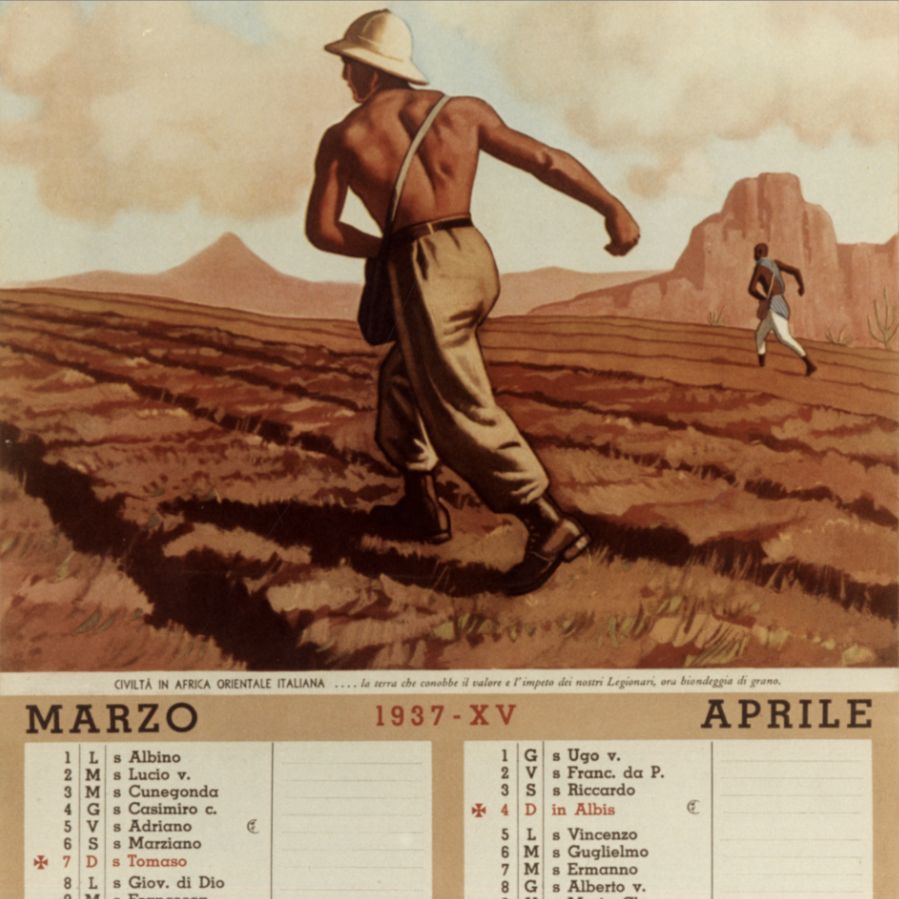

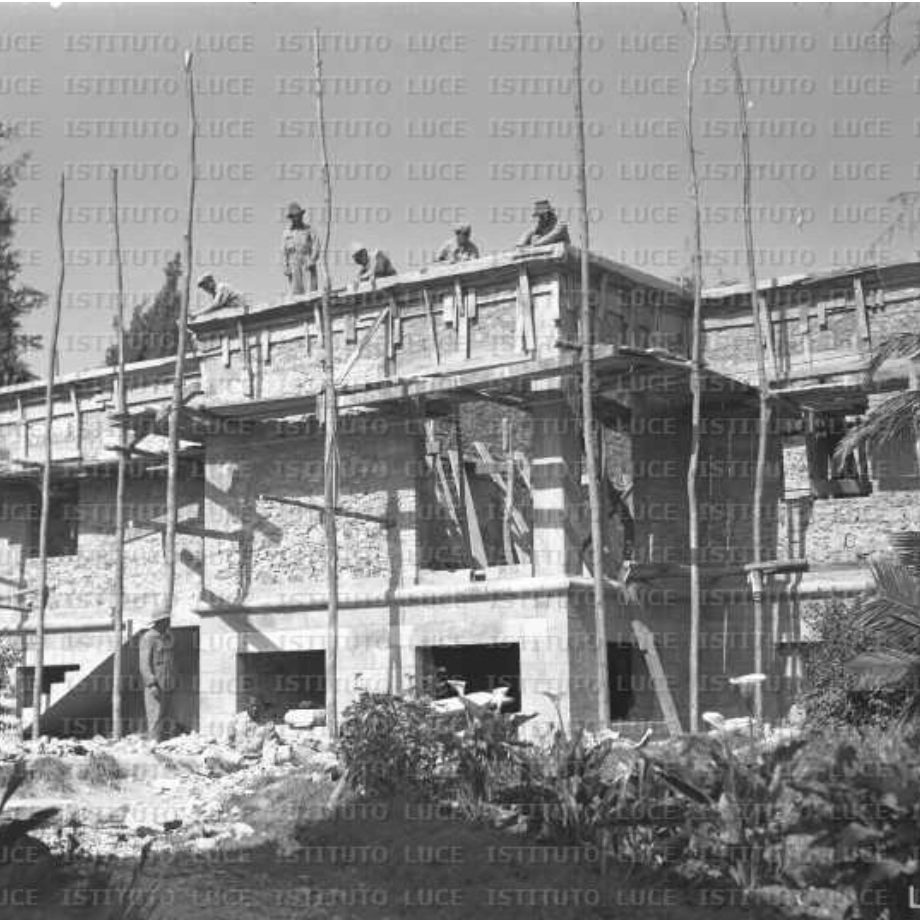

Building Pasta's Empire: Barilla and Italian East Africa

Honorable Mention for the 2023 Best Article Prize, Society of Italian Historical Studies

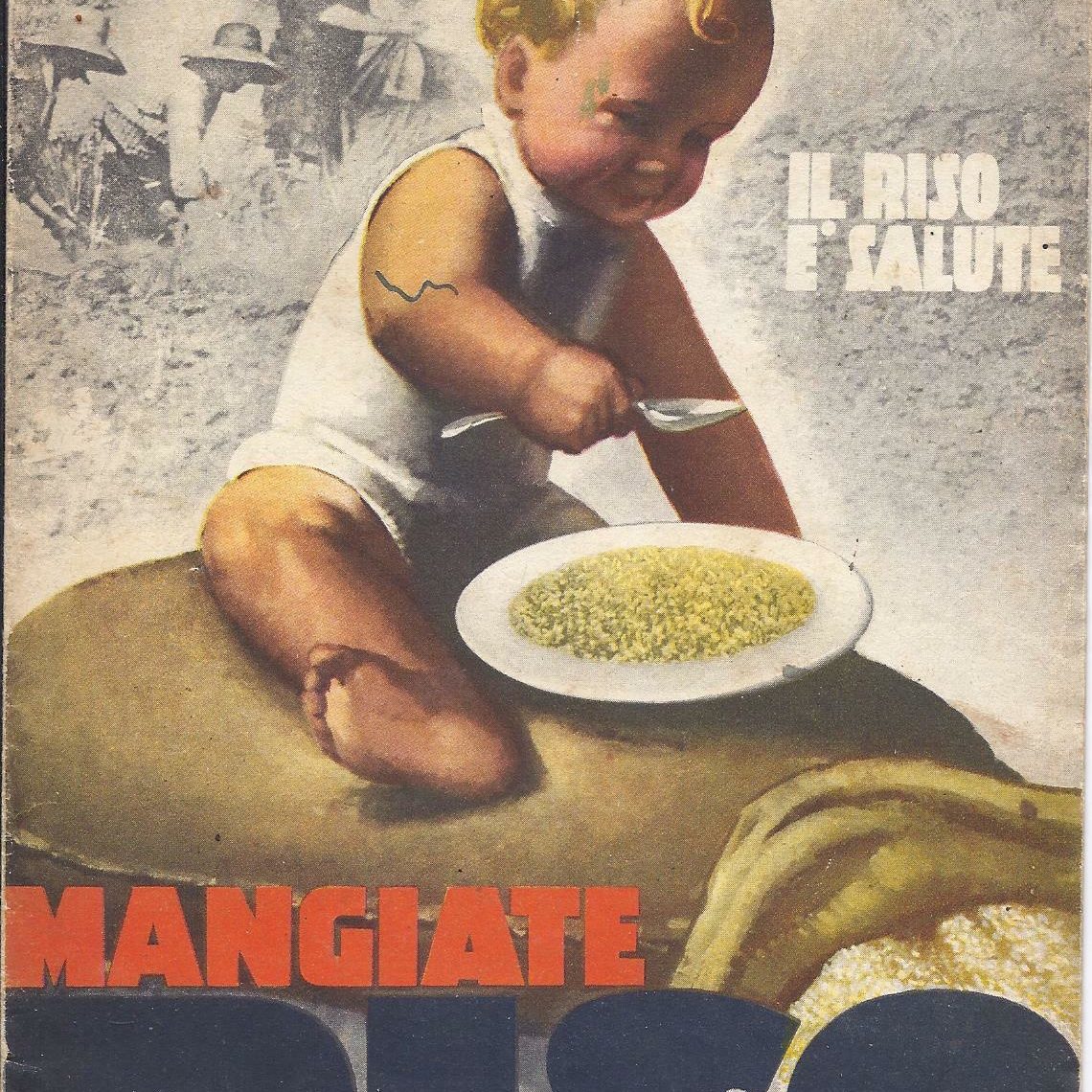

Singing Truth to Power: Melodic Resistance and Bodily Revolt in Italy’s Rice Fields

Winner of the 2017 Russo and Linkon Award, Working-Class Studies Association

Chocolate Boxes in Industrial Design

Industrial designer Emma Bonazzi designed Perugina chocolate boxes and much more.

Cut-Throat: The Battle of Adwa according to Razor Blades

Forthcoming with The Everyday Life History Reader: Working with Sources

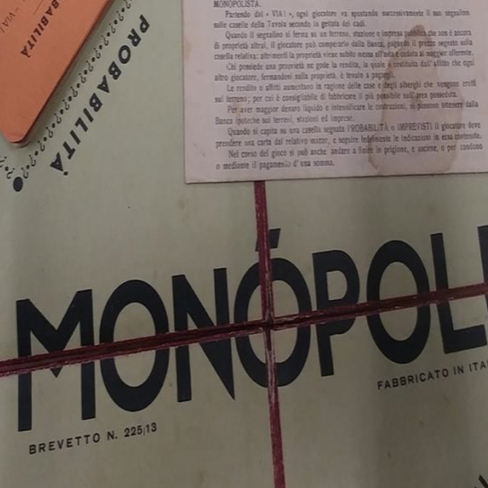

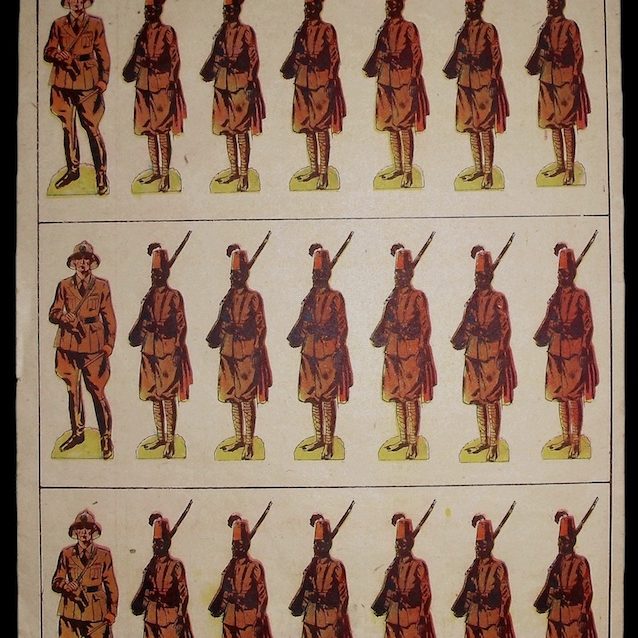

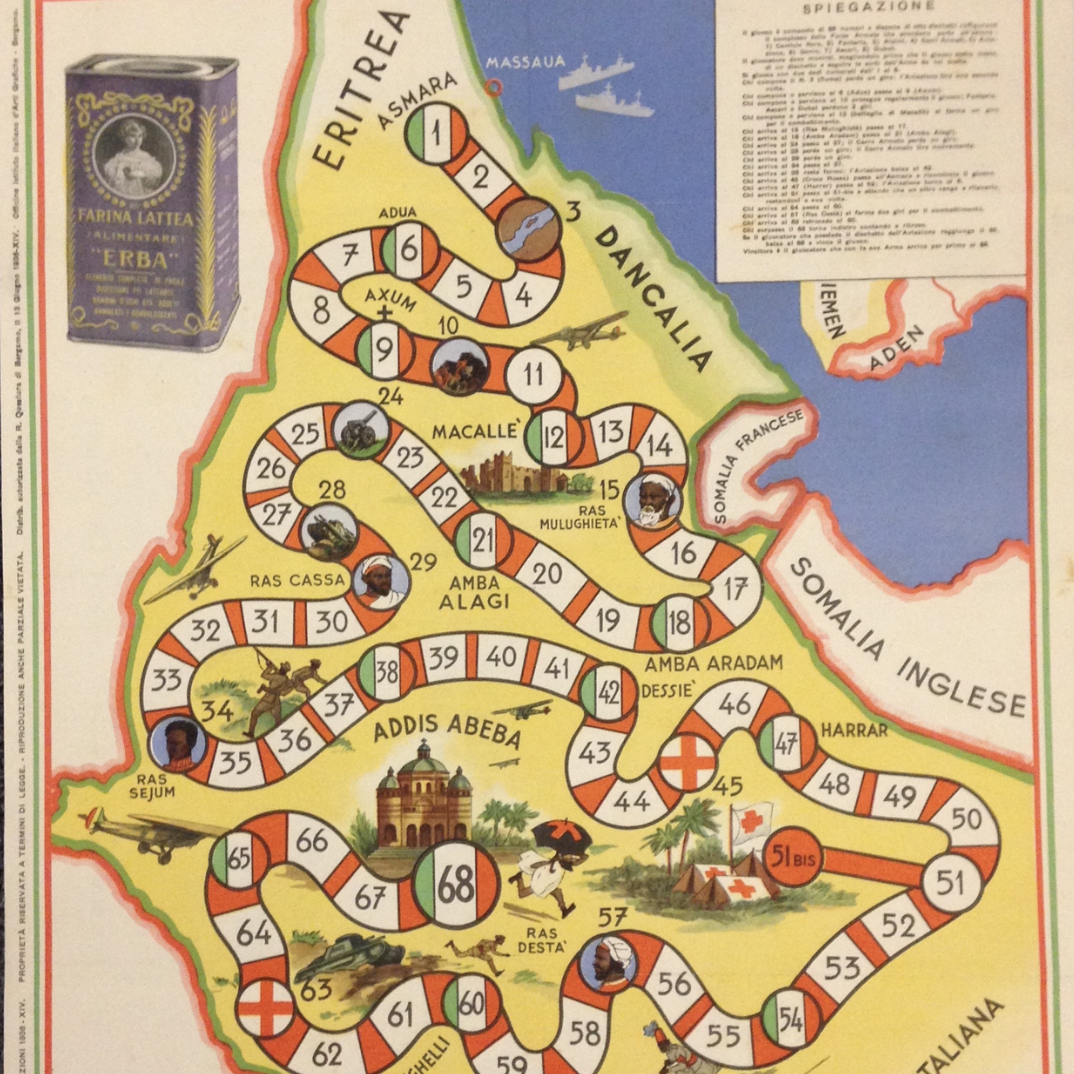

Imperial Board Games for Future Colonists

Forthcoming with Are You Game? A Cultural History of Board Games